Symptoms, Causes And Inferred Mental States

Marc Green

Most collision analyses are performed to determine the cause. This leaves open the question of what constitutes a cause.

The definition of "cause" is a knotty philosophical and psychological problem. A cause is usually defined as an

"if not for" antecedent; the consequent event would have not occurred in its absence.

This is doubtless an oversimplification1 (e.g., Sloman, & Lagnado, 2015) but even accepting the

definition still leaves an open issue. In most mishaps, "if not for" causes come in hierarchical chains.

Each link is a "symptom" of a higher level cause which in turn is a symptom of a still higher level cause.

A major question is "Where does the chain stop and ultimate causation lie?" The answer is surprisingly simple— it is a symptom that doesn't require an explanation given the investigator or the organizational goals.

In this view, causes are subjective and not objective determinations.

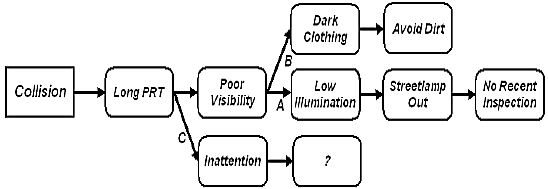

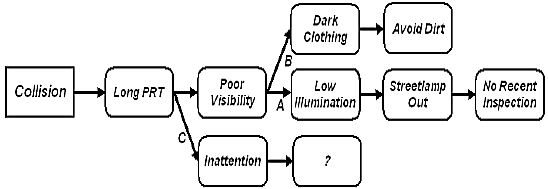

To determine causation, a causation model is necessary. Perhaps the simplest and most basic is Chain-of-Events (CoE) model. An example illustrates this best. Suppose a driver responds in 1.8 seconds to avoid a pedestrian that could have been avoided if he had responded in 1.3 seconds. What caused this collision? A causal chain to answer the question might look like Figure 1 chain A.

Figure 1 Causal reasoning chains A, B, and C where nodes to the left are symptoms of nodes to the right.

At first glance, it might be reasoned that long PRT (perception-response time) was the cause, leading to the conclusion that it was the driver's fault. This does not explain why the perception-response time (PRT) was too slow. PRT is little more than an indicator, like the gas gauge on a car.

It is not the cause of the car having no gas. It is a symptom and not a cause. As a disembodied number, PRT's main value is to those seeking to assign blame.

The slow PRT "symptom" needs to be explained. It might be explained by poor visibility. Now, slow PRT is a symptom and poor visibility is the cause. Continuing through the chain, poor visibility is then the symptom and low illumination the cause. Low light level is the symptom and a burned out streetlamp is the cause. The burned out streetlamp is now the symptom, and no weekly inspection of the light was the cause. No recent inspection is the symptom... and so on. The chain stops when the symptom need not be explained.

The investigator's goal determines where it stops. In this example, a human factors analysis doesn't need to know what caused the streetlamp to be burned out, so its cause need not be determined. The cause is then a burned out streetlamp. Perhaps a psychophysicist would simply say that low illumination was the cause and not care about the streetlamp at all. He could trace a causal chain all the way back to the statistical variations in quantal flux striking the eye as the ultimate cause, but that would not be very useful. An investigating utility company might want "streetlamp out" to be explained and continue the chain to "no recent inspection" and then find a causal explanation for this symptom.

Causes near the chain beginning generally relate to the "sharp end" of the system, the people and events that are closest in space and time to the mishap. In this case, the driver is the sharp end. Causes further along the chain relate to the "dull end," more remote entities such as those who design and maintain the system. Someone wishing to blame the driver would simply stop at the slow PRT. It would be counterproductive to continue searching for a cause that made the driver's behavior only a symptom of a greater problem. Conversely, a plaintiff attorney looking for the deep pocket would follow the chain to attribute the cause to the utility company. Conclusions about ultimate causation depend on the investigator's goal as well as on the actual events.

This is also true about choice of initial symptom. Here it is a collision. In other cases, a collision could be a cause. For example, the starting symptom for a physician or an insurance company could be a physical injury and the collision could be the cause, which then becomes a symptom of...

The example is overly simple because there is seldom a single possible causal chain. A different chain might go from poor visibility to dark clothing and then to avoid dirt (chain B). The reason that the pedestrian wore dark clothing is likely irrelevant and need not be explained, so the ultimate cause is dark clothing. However, there might be cases where the reason does matter to someone, such as when a police officer or road worker was not wearing retroreflective clothing. Then the cause might lie in the reason that the retroreflective clothing was not worn.

Of course, there can be (and usually are) multiple causation and branching chains. Mill (1874) argued that the cause is not a single antecedent but lies in the "sum of several antecedents." Moreover, causes often amplify each other, so the sum is greater than the parts (Stanovich, 1992). In the figure, poor visibility splits and has two causes. The explanation could be both a low illumination and dark clothing. Both might have been necessary for the collision to occur. It is easy to imagine that there might be more chains added, e.g., weather (fog, snow, etc.) clutter, etc. Likewise, long PRT could have gone in a different causal direction, such as violated expectation, driver age, etc.

Lastly, it might be tempting to conclude that inattention was the cause (branch C). This is an "inferred mental state" so attributing it with causation would be mind-reading. Instead, it should be viewed as a symptom that was caused by an observable event. The inferred mental state serves only as a mediating variable that could just as well be removed from the chain. Without the observable event, an appeal to inattention is just circular reasoning. It is a default explanation that attempts to attribute causation to a dispositional factor inside the driver despite the lack of any evidence. If the driver were looking away from the road to text, then that is the cause of long PRT. The utility in "causes" such as "inattention" is as shorthand descriptors. They can usefully serve as a convenient umbrella term that describes the effects caused by a range of different behaviors such as texting and opening a water bottle, but it is not an empirical cause that can be obtained without mind-reading. A little thought will reveal that circular reasoning is common in the assignment of causation - and blame.

On the other hand, general umbrella terms risk conflating distinctly different behaviors that have different effects on safety.

For example, the term "distraction" is often used indiscriminately to describe a wide range of fundamentally different behaviors. This is why it has become necessary to split the term into "manual distraction," "cognitive distraction" and "visual distraction."

In sum, every event is a symptom of one or more events higher in the chain and the cause of a lower event or events. The chain's end (and start) depends on the investigator's goal. The ultimate cause is a symptom that need not be explained. Different people with different goals may stop the chain at different points or may construct different chains. The determination of ultimate causation is highly subjective and not an objective fact.

Endnotes

1 Hume (1748) went further. He concluded that the three principles of causality are priority, contingency, and contiguity. Priority means that the cause must precede the effect. The contingency principle says that the cause the effect only occur when the cause is present. However, the contingency need not be perfect so this can both mask true causes and create illusory ones. Lastly, the contiguity principle says that the cause must be close in space and time to the effect. In road collisions, this principle is often broken. For example, a collision might occur because of a design decision that was made years before the event. Still, humans largely judge causation by "spatiotemporality" as explained here.

.

.