Distracted Pedestrians and Bicyclists

Marc Green

Distraction is a common cause of accident on the roadway. Distracted drivers have long been a topic of study by researchers and a target of sanction by authorities. Until recently, however, there has been relatively little notice of other increasingly distracted road users, pedestrians and bicyclists. The list of research studies on driver distraction number in the many hundreds and possibly thousands. However, the number of pedestrian distraction studies is far smaller, although growing. Bicyclist distraction studies are also beginning to appear with results similar to those found for pedestrians.

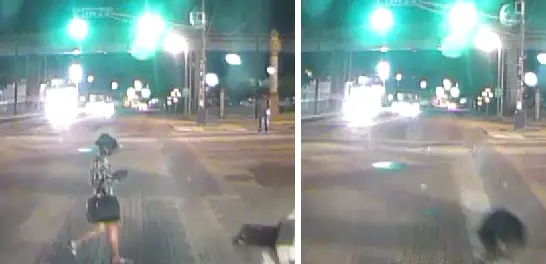

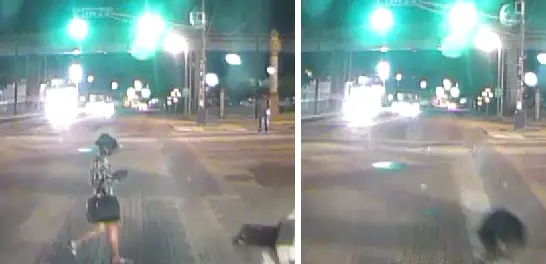

The image below shows an example of egregious pedestrian distraction. The camera is pointing forward from a bus. The left panel shows the pedestrian

focussed on her phone. The right panel, taken a moment later, shows that with the bus only a few feet away, she still kept attention downward toward the phone and did not look up. She did not sense a bus-sized object coming toward her a few feet away. Note also that the green lights face the bus, so the pedestrian was not only distracted but was also crossing against a red traffic light.

Below, I provide a brief overview of the limited existing research concerning distracted pedestrians. I focus on distraction caused by cell phone use, since there is very little research specifically on distraction caused by mp3 players and other electronic devices. However, it is possible to make some inferences that go beyond the current research because they are warranted by either studies on distracted drivers or by the extensive general research literature on perception and attention.

Cell Phones

The limited current research suggests that cell phone-using pedestrians:

- Walk slower;

- Are less likely to notice other objects in their environment, even if they are highly salient;

- Select smaller crossing gaps in traffic;

- Are less likely to look at traffic before starting to cross;

- Are less likely to wait for traffic to stop;

- Are less likely to look at traffic while crossing;

- Are more likely to walk out in front of an approaching car;

- Are more likely to be inattentionally blind; and

- Pay less attention to traffic (children).

None of these results is surprising. Attention is a zero-sum game, so the more attention paid to one task, the less available for other, concurrent tasks. This basic fact allows for some reasonable predictions. For example, "intense" conversations are more distracting to drivers, and there is no reason to believe that pedestrians escape this effect—intense, important or emotional cell phone conversations should be more distracting. The pedestrian will also likely be more distracted when increased attention must be paid to the call because the connection is poor, the background is noisy, etc. The very act of holding the phone can limit the visual field. (In fact, I was once almost hit by a driver pulling out of a driveway because her cell phone blocked her view in my direction.) Further, even simple tasks such as maintaining balance and walking require attention, so distracted pedestrians will be more likely to suffer falls. No study has examined the pedestrians during dialing or texting, but strong distraction effects are likely. You can't simultaneously look at traffic and at the keypad.

Mp3 Players

Even in the absence of specific research, it is reasonable to believe that mp3 players cause both sensory and cognitive distraction. At the sensory level, listening to an mp3 player through ear buds, and especially earphones, masks sounds such as warnings, approaching vehicles, etc. Louder music will create more masking. Moreover, additional cognitive effects are almost certain to occur. More distraction should occur when the pedestrian is listening to a book-on-tape, etc. because the listener processes the audio stream for meaning. Music with lyrics still requires some attention, if the listener is cognitively processing the words. Instrumental music requires no linguistic processing and should cause the least distraction. However, it can still distract if the listener analyzes the music, as a musician might. The tempo and rhythm might also cause a distraction. Of course, the pedestrian will likely be highly distracted when operating the mp3 player, especially if he must look directly at it.

Smartphones

Research on more attention-consuming smart phone activities such as texting, emailing and surfing is just coming off the press at an accelerating rate. Unsurprisingly, studies also found more extreme versions of the same behavior exhibited by conversing pedestrians (Lamberg & Muratori, 2012). As with drivers, texting, emailing and internet surfing are the perfect storm of distraction—intense foveal concentration to a small display requiring good acuity while performing a task that involves deep cognitive processing for an extended period. The recent studies suggest that texting increases pedestrian collisions (Schwebel, Stavrinos, Byington, Davis, O'Neal & de Jong, 2012).

Texting pedestrians walk slower (Schabrun, Van den Hoorn, Moorcraft, Greenland & Hodges, 2014), delay initiating crossing (Banducci, 2015; Banducci, Ward, Gaspar, Schab, Crowell, Kaczmarski & Kramer, 2016), deviate from a straight path (Lamberg & Muratori, 2012) and have slower reaction times (Masuda, Sekine, Sato & Haga, 2014). They are 3.9 times more likely to exhibit "unsafe crossing behavior" (Thompson, Rivara, Ayyagari & Ebel, 2012) and much less likely to look for approaching traffic (Fitzpatrick, Gómez, Knodler, McKinnon, Pires, 2015). Moreover, unsafe street crossing is inversely related to the amount of texting, as measured by the number of head turns toward the device and the number of characters typed (Banducci, 2015). The one study (Byington & Schwebel, 2013) of mobile internet use on smartphones found the same risky behaviors exhibited by texters.

I have seen the consequences of such behavior. The case of the pedestrian shown in the figure above is but one example. In another, a texting teenage pedestrian was unaware of wandering out of a crosswalk into an intersection where he stopped and was then struck. Lest anyone think that only younger pedestrians are injured due to distraction, the literature contains cases of pedestrians as old as 72 years of age (Edell, Jung, Solomon & Palu, 2013).

Lastly, bicyclists are often distracted. An observational study (Wolfe, Arabian, Breeze, & Salzler, 2016; see also self-report data from Useche, Alonso, Montoro, & Esteban, 2018) found that almost a third of bicyclists were distracted, with the number reaching 41 percent during rush hour. However, another phone interview study (De Waard, Schepers, Ormel, & Brookhuis, 2010) reported a much lower percentage in the single digits. In contrast, a controlled research study found that 25 percent of test bicyclists responded to a text message while pedaling, although some performed compensatory behavior (Nygårdhs, Ahlström, Ihlström, & Kircher, 2018).

The effects of technology on bicyclists are similar to those on pedestrians-more unsafe behavior (Wilbur & Schroeder, 2014). When using a cell phone, they engaged in more risky behavior and more often forced a vehicle driver to perform an avoidance response (Terzano, 2013). Bicyclists also pedal slower when using either hand-held or hands-free cell phone (De Waard, Edlinger, & Brookhuis, 2011). However, the type of phone might be more important for bicyclists than for pedestrians. Since bicyclists need their hands to steer, they should be more impaired by a hand-held phone than a hands-free phone (Schepers, 2007).

This distraction translates into a higher collision probability (Ichikawaand & Nakamara, 2008). One study (Montoro, 2014, cited in Useche, Alonso, Montoro, & Esteban, 2018) concluded that distraction was a factor in "up to" 89.3 percent of the 25,439 examined bicycle crashes. Another (Goldenbeld, Houtenbos, Ehlers, & De Waard, 2012) found that self-reported crashes increased by 1.4 to 1.8 for younger riders, but there was no effect on older bicyclists. Other data put the number around 4 percent (cited in SWOV Fact Sheet, 2013). These data originated when smartphone use was less common. Lastly, the distraction likely played a bigger role in single-vehicle crashes, which constitute a much greater percentage of mishaps for bicycles than for vehicles.

Conclusion

The number of pedestrian deaths and injuries is on the rise and will likely accelerate as more pedestrians use increasingly sophisticated, and attention absorbing, hand-held mobile devices. There is already discussion in some government assemblies as to whether use of such devices in crosswalks should be made illegal. Stay tuned. It looks like the driver distraction scenario is about to repeat itself.

.

.